If you think of the natural world as a library with many volumes—as many volumes as there are species of plant and animal, or types of weather, or varieties of topological or geological phenomena—that would be correct. But that understanding would be limited by your frame of reference.

You imagine that there is one book for each of these. In fact, for each there is a library such as those you have for the sum of human knowledge. There is a complete library for what the spring peepers know, for what they remember, what they dream and what they hope for, and their prophecies of what may come to pass. The wind speaks volumes and it remembers volumes. It carries within it the traces of all that it has passed over, and the wisdom of that passing.

And so your fear of losing all that you have and all that you know, although that fear is understandable, is based on a misrepresentation of your world. Human knowledge is the smallest knowledge, the briefest knowledge, the knowledge mostly given over to knowing itself. The rest of knowledge—what the plants and animals, the elements, and the invisible beings have—is an arrow pointing outwards.

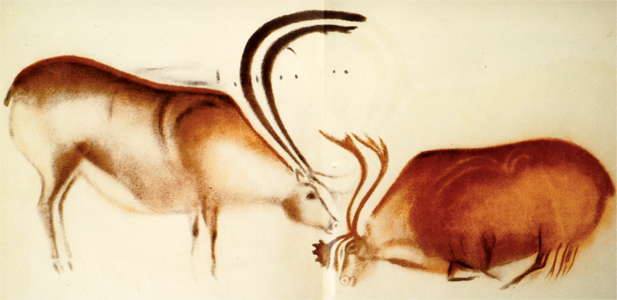

The acorn doesn’t know itself; it knows what the world thinks about it. It knows its value to the world and its place in the world. Human beings were once like this. That is why your ancestors rarely painted themselves on the walls of their caves.